Real Estate Considerations for Life Science Companies

Columbia University Irving Medical Center William Black Building Laboratories

CHRIS COOPER

Concept rendering of incubator facility

FCA

By: Wan C. Leung

Life science includes many specialties in medical fields such as biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, environmental and biomedical devices, therapeutics, and biomedical technologies. The commercial real estate needs of these companies are similarly varied and complex. While start-ups usually seek small generic lab space, more established enterprises typically require large build-to-suit spaces for state-of-the-art production and quality control facilities. Similarly diverse are life sciences landlords, who range in size from large real estate investment trusts (REITs) and real estate developers to smaller building owners that are hoping to reposition their buildings into lab space.

The balancing act between lease arrangements and the research, manufacturing, and office operations of a life science company are very different from a conventional office space. Considerations for lab-specific building utilities, hazardous and chemical limitations, and other laboratory support services are not typically part of office lease planning.

For any life science entity looking for real estate, it is critical to understand the type of space needed during the life cycle of the business. This includes looking into what location offers the most beneficial results, what to pay attention to in either old or new buildings, and finally, how the building can accommodate a design that best suits its needs.

Aligning product and business life cycle to space needs

Columbia University Irving Medical Center—William Black Building Laboratories.

CHRIS COOPER

Given the unique requirements and challenges of life sciences companies, real estate developers and owners have created specialized campuses, spaces, and products to enable these companies to navigate more easily and efficiently through the continuum of the product life cycle.

1. Incubator/Accelerator

These types of spaces are geared towards early-stage companies developing and testing the efficacy of their product. Funding is associated with the Founders and Series A stage. During this period, the founders must demonstrate commitment. The usual method is for the founder to invest its own funds. This message will resonate with Angel investors, those looking to invest, be involved early, and might believe in the big idea. Since funding is limited, these companies may not be willing to invest in building out space or make long term lease commitments. These incubator/accelerator suites typically involve pre-built, generic laboratory spaces, which can range from one bench in a shared suite to a 15 full-time equivalent (FTE) and 10,000 sq. ft. dedicated laboratory suite. These laboratories are generic, which typically means that landlords are comfortable agreeing to very short-term leases knowing that the buildout has substantial residual value for the next user. This flexibility enables tenants to consume only the space they truly need while giving them the ability to transition into larger, more customized spaces as they progress through their business life cycle.

2. Graduation space

When a company demonstrates certain levels of success in its research and has secured its initial Development and Series B rounds of funding, it’s often time to move on to a larger, more bespoke space designed to its specific needs. The timing here is critical––early-stage funding will not last forever, and every day that is lost getting up and running in the new space delays the ultimate commercialization of the product.

3. Clinical/Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP) space

BioTrial North America headquarters.

CHRIS COOPER

Unlike incubator and graduation spaces, which are exclusively limited to research and development, clinical/cGMP space includes manufacturing and space, warehouse space for storage of the raw materials and finished product, and supporting continued development and quality control laboratory areas. The design and construction of the space must meet established federal standards for the results to be accepted by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other regulatory authorities. The further the development moves, it means progress is being made, and investors, usually venture capital, likely have committed during early funding stages to continue supporting the development. In this sense, it is a matter of steady advancement and moving to clinical production and trials.

4. Commercialization space and exit stage

This stage is referred to as the “exit stage,” which (while it might seem strange) is a term for success. The idea now needs investments at much larger scales to support continued growth and product development. It can exist as a private for-profit entity, though unlikely, or it can seek to sell to another entity or become a publicly traded company—commercialization of products is part of the equation.

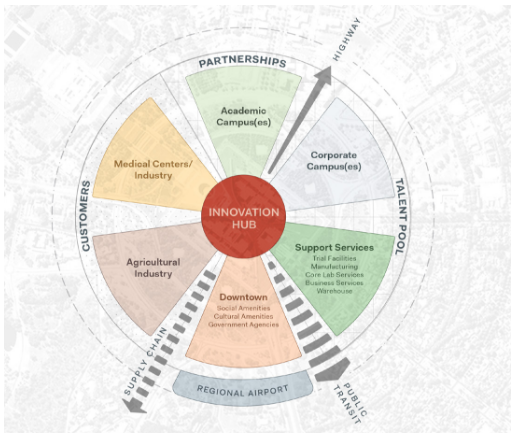

Anatomy of an Innovation Hub: not all neighborhoods are equal

3M+KCI LifeCellPilot and manufacturing facilities.

JEFFREY TOTARO

As the life science sector explodes across the country, entire buildings and even neighborhoods are evolving and transforming to attract and support these companies and their workforces. Life science companies are often looking for a home where they can be part of a larger community of shared interests and goals—an Innovation Hub. These communities offer beneficial collaboration, shared resources, and a greater talent pool to support their important work.

What characteristics are essential for a life sciences “Innovation Hub”?

A community with a shared focus on research, development, and best practices; that can accommodate and support all phases of their product development and business lifecycle.

A place that promotes and facilitates partnership opportunities with local economic development, universities, healthcare systems, technology firms, and pharmaceutical companies.

A place that can attract, engage, and inspire a rich talent pool of workers.

A place where regulatory requirements can be easily met.

Finding the right facility and understanding three types of building readiness for life science

Options for space can range from new, purpose-built laboratory facilities to re-positioned buildings whose original purpose may have been as an office, manufacturing/industrial or even big box retail or department stores. While retrofits of existing buildings can save significant time and money vis-à-vis new construction, these conversions are not without their risks and challenges. Proper due diligence of base building infrastructure and services is critical to avoid problems down the road.

Life sciences buildings can generally be broken down into three different categories. It is critical that potential tenants understand the true level of preparedness of each building it is considering as it will have a major impact on both the project schedule and budget. This is especially important for adaptive reuse buildings.

Designing your lab and how much space will you need

Anatomy of an Innovation Hub.

FCA

Once a location is more refined and narrowed, it is time to think about how much space is needed, the design, and the timing of construction and occupancy. Since each square foot is costly, seeking the help of a professional laboratory planner and architect will help guide this basic premise.

The space program

The first step in designing your space is determining what kind of space and how much of it is needed. This involves developing a space program which considers current and projected headcount and an assessment of the business operations, including safety protocols, and employee work functions. The planner will use this program to quantify and help develop a potential layout.

Laboratory vs office Space: Typical life science programs range between 40 percent office and 60 percent laboratory to 60 percent office and 40 percent laboratory. These mixes are not always static and can change over time as the product and business life cycles change. In some instances, it may be cheaper and less disruptive to incorporate the necessary infrastructure improvements that will be required for future conversions (i.e., office to laboratory) during the initial buildout rather than making these modifications later.

Other types of space: While office and basic laboratory spaces make up much of the space program, in some cases, other specialized support functions such as vivarium, environmental chambers, imaging suites, clean rooms, and other specialized spaces may require up to 20 percent of the total planned area.

FCA

Life science spaces and leases are unique and highly complex, and changes as the business grows or takes a different direction. The preceding only touches on the initial broad issues, because of this, each potential facility should be carefully customized to the needs of the tenant and commercial real estate owner. Taking on a partnership approach will serve the needs and interest of both parties. Understanding the requirements of the life science facility and the ability of the building and location, will promote successful discussion and business decisions.

Wan C. Leung, AIA, is principal with FCA. He can be reached at wleung@fcarchitects.com.