Across The Table: The Most Common Specification Mistake

“Water’s leaking from the lab faucets again.” Facilities staff constantly have to fix a problem that wouldn’t exist if lab planners specified vacuum breakers properly.

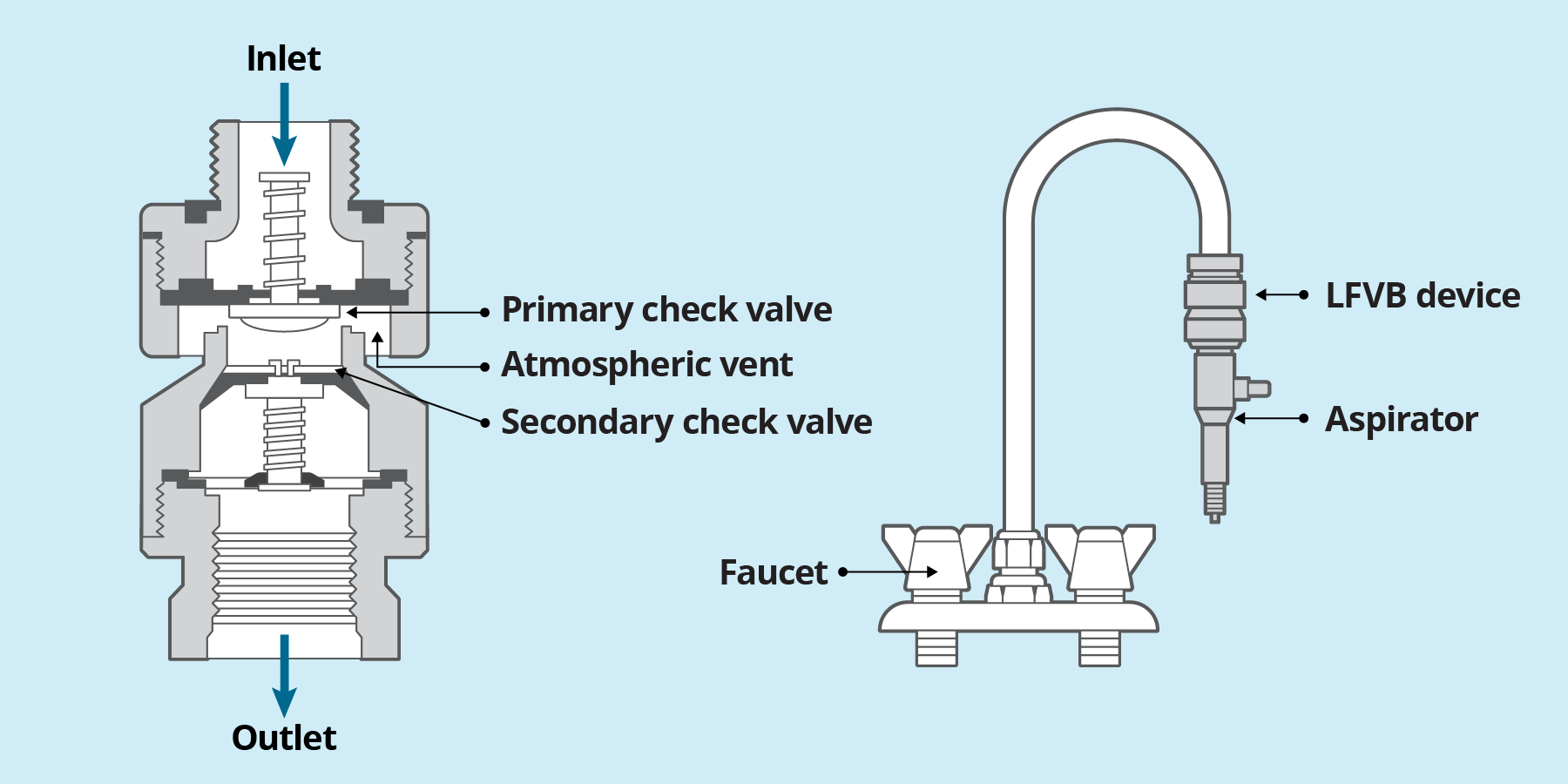

A hose might be connected to the serrated end of a lab faucet, with the end left in standing, chemical-tainted water. If back-siphonage occurs, this contaminated water could be backed up through the faucet, into the plumbing system, or even into another laboratory. To prevent back-siphonage, a properly designed atmospheric vacuum breaker [AVB] or a laboratory backflow preventer [LBP] should be installed on the faucet. If you have leaking faucets with water on worktops, you likely have an AVB. If your AVB leaks, it may be functioning properly!

Or, it may not. Of the dozens of types of vacuum breakers, the ASSE International (American Society of Sanitary Engineering) has a standard for the 1001 Atmospheric Type Vacuum Breaker (pipe applied). You often see this on laboratory faucets. It is simple and inexpensive. And it often leaks for the same reasons.

The central part is the float. Water flow pushes the float up and seals it in an open position, allowing the water to continue out of the faucet. If there is a loss or reversal of pressure, the float is supposed to settle back down and provide a seal to stop backflow, such as back-siphonage from a hose resting in the water.

The float is also a key cause of water leakage. For instance,

With low water flow, there may not be enough pressure to seal the float in the open position. This could allow water to escape through the integral air vent.

Even with normal water flow, water can escape through the air vent before the float is fully sealed.

Perhaps the faucet is not installed plumb and level, leaving the float in a tilted or angled position and unable to seal completely. Water could leak.

Maybe there is scale or pipe sealant in the water. Again, the float may not seal completely. Water could leak.

You could remove the cover and remove foreign material. You could order an AVB repair kit from the faucet manufacturer and see if that solves the problem. If the problem persists, you can’t just replace the AVB. It is pipe-applied, requiring replacement of the entire faucet.

Consider this alternative. Order a standard lab faucet without an AVB. Then order and install a Laboratory Faucet Backflow Preventer (LBP, ASSE standard 1035). Most plumbing codes reference this as “Hose-connection vacuum breakers shall conform to . . .” the ASSE 1035, not the ASSE 1001. [Still, check local codes.] The LBP offers these advantages over the AVB:

American Backflow Prevention Association

If necessary, the LBP is easily replaced. Just screw it in or out of the faucet end. An aspirator or the serrated end for hose connections fit into the LBP. You won’t have to replace the faucet.

The LBP hangs over the sink. For any leakage, the water goes into the sink, not on a work surface.

The LBP is less expensive and readily available from numerous sources, not just from the faucet manufacturer.

The LBP also protects against low plumbing system backpressure. The AVB is approved for back-siphonage only.

The best solution, though, is for the architect or lab planner to specify Laboratory Backflow Preventers, not Atmospheric Vacuum Breakers. Per the ASSE, the word “Laboratory” is in the name for a reason.

Dave can be reached at dwithee@alum.mit.edu or 920-737-8477.

All opinions expressed in Across The Table with Dave Withee are exclusive to the author and are not reflective of Lab Design News.