Laboratory Design and Construction: Translating Success

By: Danny Sanchez, P.Eng., PMP

The lab manager during the review of the lab layout drawings as part of the detailed design process.

BUERAU VERITAS

Have you thought about how many different “languages” can be found in a laboratory project? Imagine you are the lab manager in charge of your laboratory renovation and there is a discussion around CFM (cubic feet per minute). How would you know if your laboratory requires 300 CFM, 3,000 CFM, or 30,000 CFM?

You could argue that these technical matters are the responsibility of other project contributors and that a lab manager does not need to know all the answers—that rationale would be correct. It is important to mention, however, that the lab manager will ultimately have to contend with the end-product of the design and construction processes. Besides, this dilemma goes both ways. For example; architects and engineers may have a hard time deciphering common laboratory terms such as XRF, NMR, ICP, HPLC, or GC, just to name a few.

The lab manager must be constantly mindful of this predicament in order to recognize communication and knowledge gaps that, if not resolved, could potentially translate into unwarranted incidents, health concerns, testing integrity issues, workflow inefficiencies, sub-standard code compliance, and even building structural failures in extreme cases. Human communication is intricate enough, all the more so when the sender and the receiver are not speaking the same “language.”

Language vs. success

Figure 1: Simplistic illustration of processes, stakeholders, and “languages” commonly found in a new laboratory construction or renovation project. The center section shows a basic representation of the main sequence of events. The lab manager role belongs within the top section whereas the bottom portion represents all other external players.

BUREAU VERITAS

There is a diverse group of minds involved in any lab design and construction project, from architect, project manager, design consultant, general contractor, to the facilities manager. The lab manager often acts as the liaison source between these numerous disciplines to ensure the needs of the lab staff are being met, while also keeping the project on track, and on budget.

In addition, different organizations coexist under the temporary project environment. Each of these organizations seeks its own goals (sometimes under competing interests). This potential adversarial relationship between project organizations [tends to] lead to conflict.

Each discipline has an associated vocabulary—represented by the multiple rectangular text boxes in Figure 1—that demands a certain level of familiarity with the domain for the receiver to effectively decode the message being sent. The interactions among all these fields of expertise are of particular significance and in many cases, the difference between project success and failure. Project success is a controversial topic that acquires yet another dimension in a laboratory construction or renovation project mainly due to the multiple complexities inherent to designing and building a high-tech facility. Moreover, success is usually in the eyes of the beholder and even more difficult to measure. Although there is no magic formula to navigate these challenging dynamics, let’s discuss some of the most notable communication interfaces through a handful of concrete examples and recommendations.

The benchmark

Figure 2: Initial Conception or Ideation phase that must precede any design or construction effort and where the Lab Manager should play a leading role in.

BUREAU VERITAS

The conception phase—as shown in Figure 2—is repeatedly overlooked and occasionally, skipped altogether, largely as a result of schedule pressures. This discovery process is critical towards documenting the organization’s strategic vision. This vision has to be translated into a mandate that ought to govern every important decision that is to follow. Case in point: It took three attempts to produce a successful design proposal for a much-needed, and safety-driven renovation project for an aging refinery laboratory. Why? The first two efforts were out-of-sync with the organization’s vision and budget, thus failing twice at project sanctioning, delaying the project by almost two years and wasting thousands of dollars in unnecessary consulting fees.

The lab manager should formally identify the executive decision-maker at the highest level, as early as possible, to extract the overall project expectations and constraints. Other key participants such as health and safety, regulatory authorities, legal, consultants, subject matter experts, and other groups sharing the facility, may need to be enrolled this early. Practical hint: if you cannot find a particular answer, you are missing a player in your team.

A formal communication channel should also be implemented at this time to facilitate the information flow and the consultation mechanism throughout the entire duration of the project. Budgets, timelines, and even the size of the laboratory are frequently determined without any consultation with the lab manager or any other relevant contributor, at times resulting in unrealistic project constraints. Perhaps the central outcome of this initial transformation is the definition of success in itself. Make every effort to capture the essence of the project into a set of conditions, goals, and needs. This “success criteria” will serve as the main benchmark against which to measure success at project completion.

The right questions

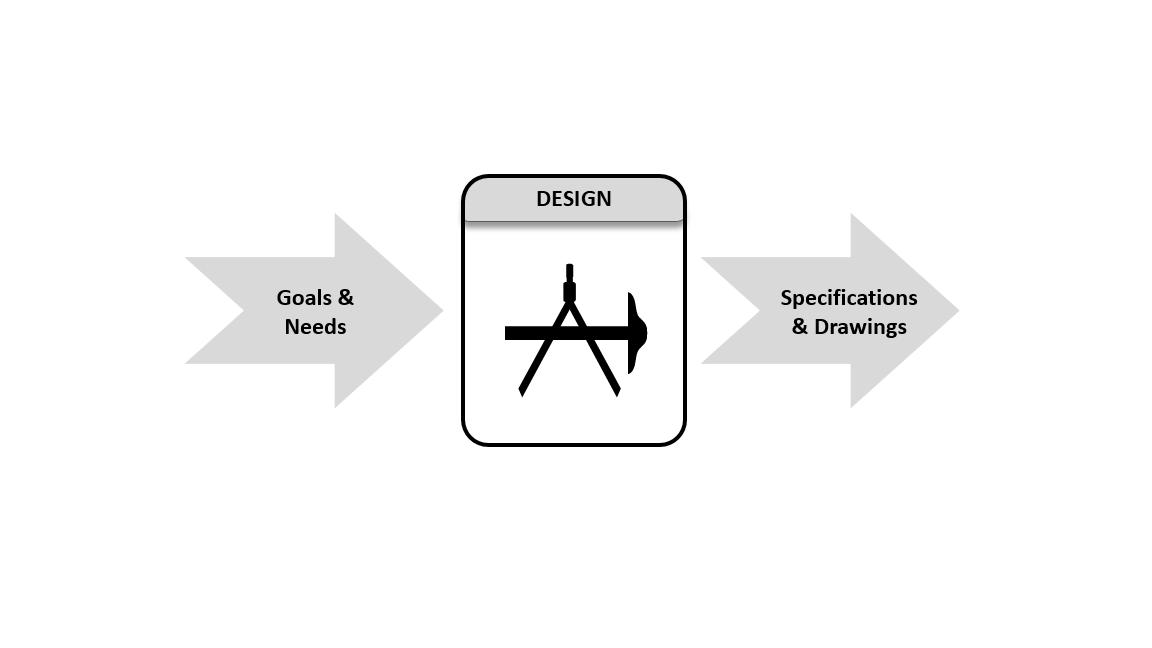

Figure 3: The laboratory design stage is where the lab manager could confront the bulk of unfamiliar technical terminology.

BUERAU VERITAS

Laboratory design involves asking the right questions and understanding the reasoning behind the answers. This means replacing the question “What do you want?” with “What do you do?” Often, perceived needs do not translate into actual needs and old ways of doing things plague the new design without being contested. The trick lies in knowing the right questions to ask. For example: you have likely encountered certain laboratory tests and equipment that are prone to generating excessive condensation of fumes such as acid, organic compounds, or just water moisture. Do you know that there are design provisions that should be applied in this scenario to manage the condensation in ventilation ducts?

Construction site walk-through involving the lab manager.

BUREAU VERITAS

The niche characteristics of the lab design process makes it difficult to find experienced laboratory design consultants locally. A few probing questions to any would-be consultant would reveal how knowledgeable they are in the dialect of lab-specific codes and standards. For example: Do you know where not to place a fume hood? Do you have to exhaust a chemical cabinet?

The lab manager must also strive to participate in the review of all significant design outputs, along with ensuring that all important decisions are sanctioned by the executive decision-maker. Likewise, the lab manager must ensure that the design team encompasses competence in all relevant fields so the technical information can be accurately mined and converted into coherent design specifications and drawings as shown in Figure 3 above.

Strong evidence from research in the construction industry reveals that one of the factors that cause construction projects to fail stems from decisions made … in the engineering and design phase. Any mistake or omission at this point will later materialize as unintended re-design iterations and expensive change orders.

Trust, but verify

The lab manager rarely has an active participation during the construction of their labs. Yet, it’s unlikely that any other player would be more skillful in quality assurance and control—the construction process requires a quality system just like your lab does. Ask to see the construction quality management plan and confirm that it clearly identifies all quality standards to be followed. Verify that construction begins with a thorough design package so it can be later used as one of the yardsticks against which to validate construction packages.

Insist on taking part in construction site inspections so you can contribute to spotting misalignments with your company’s vision and the design specifications. The sooner nonconforming work is identified, the lesser the impact, and the sooner preventive actions can be established to eliminate nonconformance. Be aware of your own costs when developing the project budget since construction cost estimates tend to exclude other disbursements that the lab owner will likely encounter namely: swing space during renovations, moving expenses, equipment rental, and temporary storage among others. Construction schedules, on the other hand, may omit steps such as regulatory compliance assessments, accreditations, and client audits that may be required before the laboratory is fully operational.

Figure 4: The construction stage as the final transformation. Note that in this simple project timeline representation, construction comprises other activities like commissioning, start-up, and hand-over.

BUREAU VERITAS

Make sure that prospective construction providers can produce a track record pertinent to your application. An animal research facility for example, differs drastically from a petrochemical commercial lab. An in-depth understanding of the special hazards found in your laboratory is indispensable in order to translate drawings and specifications into the laboratory you set out to build at the onset.

Summary

Underestimating and oversimplifying the lab design and construction venture is a widespread phenomenon that, in my opinion, is generally at the root of nearly all laboratory project failures and problems. Regardless of how small or similar your laboratory may resemble another facility, there will be many nuances that will likely have a meaningful impact on costs, future-proofing, workflows, staff experience, materials handling, storage, ventilation, hazard controls, and countless other aspects of your laboratory.

Furthermore, it is improbable for a laboratory project to be successful without sound laboratory expertise at the center of every single communication exchange. However, experience has amply confirmed that there is a steep learning curve whenever laboratory personnel enter into the design … of their own laboratories. With respect to the multitude of “language barriers” aforementioned, use the success criteria as your compass throughout the project life cycle. If a particular technical term seems foreign to you, ask for clarifications on how it relates to the project success criteria. For example: How may CFM ensure a safe laboratory operation?

Effective, transparent communication and pervasive collaboration, among all project stakeholders, is paramount to translate your company’s vision into a safe, resilient, and functional laboratory for years to come.

Danny Sanchez, P.Eng., PMP, is senior manager of technical services with Bureau Veritas.