Learning from Retail

By: Jeff Talka, AIA, LEED AP

Women's Care Florida diagnostic lab fit-out using prefabricated and pre-wired panel systems; eliminating need for power poles to equipment.

JEFF TALKA

All around the country, developers have been creating what we like to call “strip malls”—typically, one-story commercial structures divided into “stores” which may be occupied by a variety of retail uses. They are normally organized fronting on parking with good visibility from a major vehicular thoroughfare. Occasionally, there will be an anchor store which provides an identity to the development and becomes a “draw” for the other smaller retail tenants in the project.

The laboratory market can learn from how these developments are organized physically, programmatically, and operationally. They embrace many of the attributes required in good lab designs: modularity, adaptability, scalability, functional independence, and cohesion of purpose. These strip mall facilities come with a common kit of parts which may be amended to achieve a certain purpose of use, and they can be independently modified without affecting their adjacent uses or tenants. In order to achieve flexibility and scalability, developers will usually set up a modular approach to the facility—mostly a warm dark shell with a fixed set of infrastructure components. For instance, for every 5,000 sq. ft. of space, the tenant utilities may include a 5,000 CFM rooftop air-conditioning unit, a 1 in. cold water service, and a 200 amp electrical service; all individually metered or sub-metered. In some instances, a gas service may be available. Sanitary sewer connections are provided on regular intervals.

By providing just basic services, the developer is able to lease space to a variety of tenants. Individualized fit-outs are accomplished by the tenants themselves. Based on the complexity and environmental requirements of the use, the infrastructure provided by the landlord is sufficient. A shoe store, jeweler, stationery store, and clothing store will have very similar requirements. The location of these tenants is not dependent on special infrastructure requirements, so they are interchangeable. In the case of a tenant with more specialized needs, such as a restaurant (ventilation and exhaust), medical office (water usage), or laundromat (water, drain, and ventilation), these special requirements are additive to the basics provided by the landlord and paid for by the tenant. Based on the lease arrangements, the tenant may absorb these additional costs or they can be provided by the landlord and paid for via increased lease costs. For instance, a restaurant tenant will need to provide additional ventilation, exhaust fans, grease traps, and fire suppression systems, which would not normally be a basic utility offering. If the use changes and the added infrastructure is no longer required, it can be abandoned, removed, or left in place for the next tenant.

This approach can be applied to research laboratory facilities in a couple of ways. For new construction, acknowledge that flexibility and adaptability are based on a balance of cost and amenities. To maintain a flexible project future, the amount of services to be provided in the base building should be able to support basic science. Pathways for additional services should be provided, although the actual installation of these services can be made on a case- by-case basis as needs arise, based on the specific science to be conducted. Following an approach that reduces the amount of infrastructure can result in a facility with a lower first cost, compared to a “traditionally” constructed facility with comprehensive central services. By making the choice between central utilities and point of use, there is opportunity for flexibility and economy.

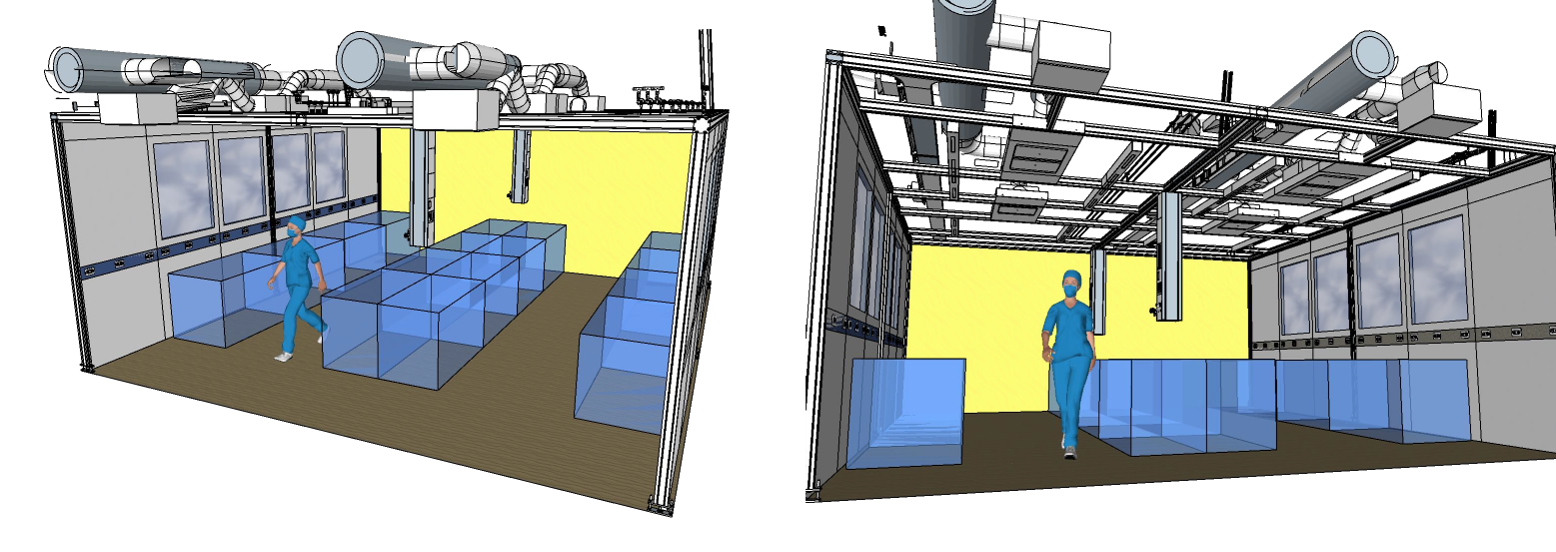

Prefabricated modular free-standing system in development for use in quickly transforming open spaces such as found in retail to laboratories.

WALDNER, INC.

Adaptive reuse of retail facilities for the construction of new lab spaces may be accomplished in an accelerated manner, and in a cost effective manner as well. The economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in the availability of existing retail locations, which may be converted economically and quickly to research lab space—perhaps even to be used in the race for a COVID-19 vaccine. Some of these opportunities may present themselves as existing restaurants whose use can be converted to laboratories, for example. Use due diligence to confirm existing conditions and identify what infrastructure supplements are required.

Existing retail facilities should be evaluated for:

Floor loading: Most retail is slab on grade and should be able to accommodate floor loading and resist vibration.

Roof loading and access: Retail roofs are typically lightweight steel which may need to be reinforced if additional mechanical equipment is to be installed; the proximity of the roof surface to the space below is important.

HVAC: Most retail rooftop units are split systems and of the recirculating types. They may need to be supplemented with 100 percent make up units

Exhaust: New fans and stacks may be required, at a safe distance from outside air intakes.

Electrical service: This needs to be identified by voltage, amperage, and phase. Some mechanical equipment may require 208-volt or 480-volt power, which may not be available. The decision will need to be made whether to bring in a new service of engineer equipment with the service available.

Water service: Flow rates and volumes should be determined and evaluated. In most retail situations, the service should be adequate. Purified water such as RODI should be considered as point-of-use systems for flexibility and cost.

Piped gases: Most likely there will be no central gas services, such carbon dioxide or nitrogen. These can be provided either as point-of-use or piped from a central location like a service dock, which all retail facilities would normally have.

Waste systems: The need for point-of-use acid neutralization versus bulk external systems.

In approaching the design of a laboratory in a retail envelope, separate the fit-out from the existing construction to the greatest extent possible. Employ flexible prefabricated components and construct them inside the “warm dark shell.” There are many products on the market that may be utilized to construct the lab space with minimal structural disruption to the building shell. Utilizing a kit of parts approach will reduce construction time, be cost effective through factory-based prefabrication, and will be adaptable and easily reconfigurable. Ceiling systems organized with regularly spaced members and ceiling utility panels present a “plug and play” approach. The system itself provides pathways for utility distribution, service integration, and a sub-structure to which other systems such as demountable partitions may be attached. Through the use of ceiling utility panels, the field trades stop at the ceiling and do not need to be continued in the field through walls or casework.

Demountable partition systems, which are pre-wired and pre-plumbed, are readily reconfigurable and may be serviced from the ceiling utility gridwork. These partitions can be integrated with lab casework systems or may provide final connections such as receptacles and data ports in the system themselves. These partition systems will quick-connect, either above the ceiling or to the services in a utility grid. Prefabricated mobile laboratory casework may be prepared with services factory installed. These systems can be connected to ceiling utility panels or may be configured to quick-connect to partition systems. There are other service distribution approaches which exist which may allow the mobile casework to be independent of services. One such system uses a mobile pedestal on casters, which quick-connects to ceiling utility panels. These pedestals contain the services. The resulting installation does not require the lab benches themselves to have services. They can be lab tables.

By looking at retail facility attributes and comparing them with the needs of research laboratories, common threads will be identified to develop a quick response lab in an existing facility. The keys are modularity, adaptability, and flexibility. The final definition of flexibility will be reflected in the components used in the lab fit-out. The existing facility should not get in the way of the science, if a systems approach is utilized.