Ramping Up Lab Operations During COVID-19

The speed with which new circumstances and changing requirements are communicated to lab teams will make the difference in maintaining an ongoing project or being forced to shut down.

COOPER CARRY

As more and more states institute phased re-openings during the COVID-19 crisis, architecture companies, design firms, and lab managers are developing plans for how they will handle business going forward. The unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, however, has left many firms wondering exactly what they need to do in order to bring people back to the office—and laboratory—in a safe, efficient manner.

Cooper Carry, a design firm based in Atlanta, Georgia, decided to put together a COVID-19 rapid response team to assist lab managers and owners as they develop these plans. The team includes members from health and safety consulting firm ORC HSE, air flow management company 3Flow, and scientific furniture and equipment provider Nycom, in addition to Cooper Carry design experts. Their goal focuses on reprogramming labs to comply with current health recommendations, in order to develop a comfortable, collaborative environment for scientists when they return to the workplace. This includes measures such as social distancing protocols in the lab, creating additional storage solutions, and regulating air flow.

Mark Jensen, principal in Cooper Carry's science + technology studio, says that the idea for the rapid response team evolved after he attended a virtual town hall on returning to the operational lab environment during COVID-19, run by the International Institute for Sustainable Laboratories (I2SL). The town hall’s speaker lineup, says Jensen, included various experts from a wide cross-section of laboratory end users and operators, representing industries such as big pharma and biotech, academia, and consulting firms. After speaking with some of his own clients, Jensen realized that it would be useful to take these ideas, along with his own, and develop a plan to help guide others. “The idea of compiling best practices, what the community’s talking about, into something that was a bit more coherent than a somewhat stream of consciousness transcript from a town hall—that was the beginning of this,” he says. “The whole idea was to try to get something out quick to the community to say, ‘Hey, there’s a lot of different ways to skin this cat, and every lab is different, but here are some best practices. We’re here to help you in any way we can.’” He pitched the response plan idea to one client with whom he had previously been discussing return-to-work strategies—laughing, he says that the client’s response was, “You’re scratching where I’m itching,” and then asked Jensen to send over the plan as soon as it was ready.

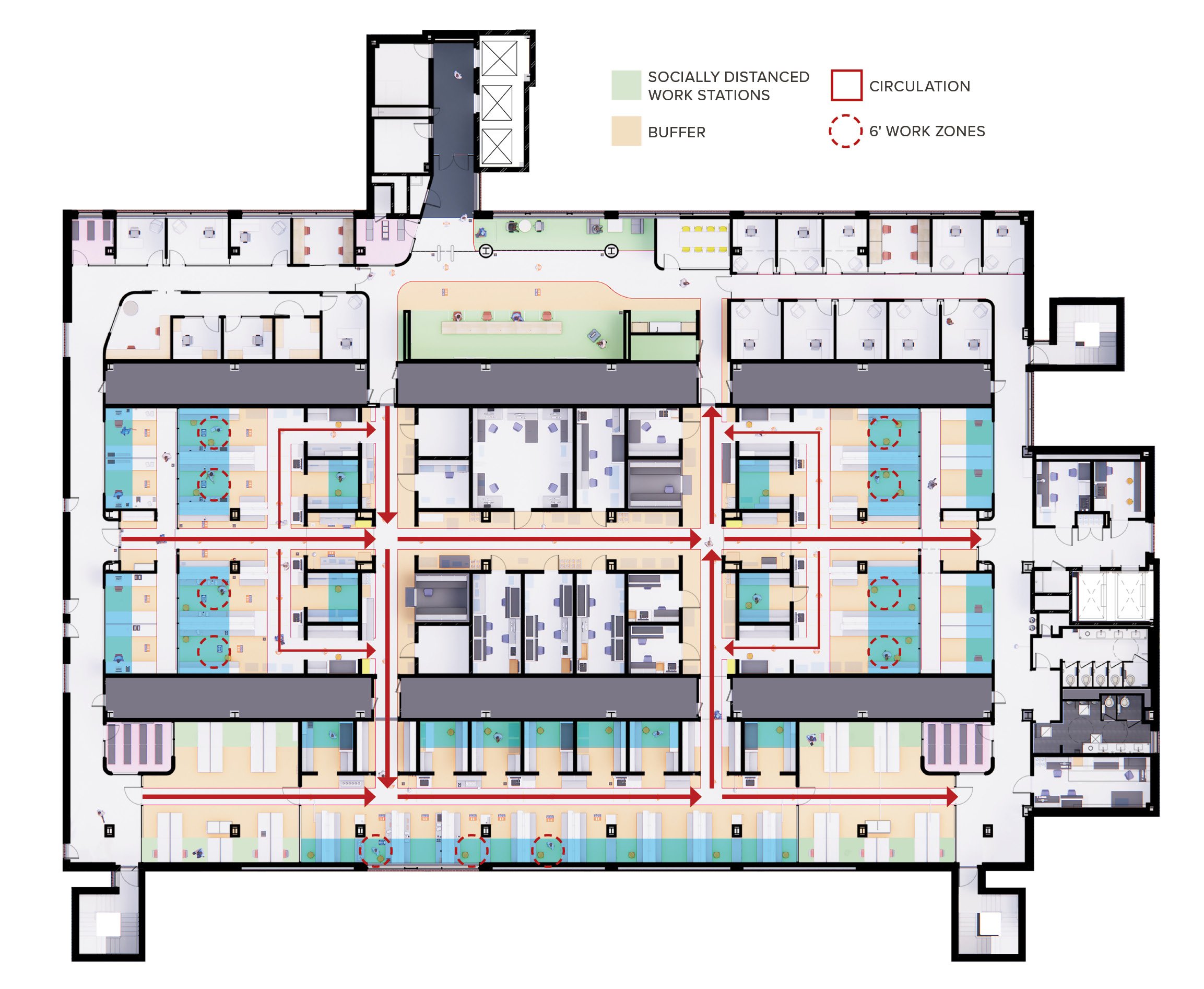

It is important to set up directional movement in the laboratory to help prevent cross contamination. If you have aisles, ensure cross connections so people can walk one direction down an aisle and the opposite direction in the next aisle.

COOPER CARRY

Occupational safety and health professionals use a framework called the “Hierarchy of Controls” to select ways of managing workplace hazards. There are trade-offs to each type of control measure when considering implementation, effectiveness, and cost.

CDC NIOSH

Brent Amos, principal with Cooper Carry’s science + technology and higher education studios, is another member of the rapid response team. He had had conversations with clients prior to the I2SL town hall, he says, who had pretty much shut down when the coronavirus started spreading throughout the US, and they were eager to develop their own protocols for returning safely to the lab. “We had the thought, ‘How can they get back into the labs and operate them?’” he says. The clients wanted to know how to go about social distancing, and wanted to learn more passive ways of operating within the lab. Amos worked to create diagrams for the clients that detailed strategies, such as how to maintain 50 percent of the lab and tape off unused areas. Then Jensen came along, Amos says, and suggested the task force to develop a comprehensive plan for clients. “It came together pretty seamlessly,” says Amos.

Much of the inspiration for the Guide to Ramping Up Laboratory Operations came from other organizations’ existing plans. Jensen cites the CDC, ASHRAE, and OSHA as resources he and his team consulted when developing their guide. Another source, perhaps surprising to some, is the meat industry. It’s not the same as laboratory research, says Jensen, “but the guiding principles are very applicable and similar—develop an assessment and control plan, the hierarchy of controls from OHSA and the CDC and other organizations, frameworks that they’d had in place for decades—so that’s what we built on.”

The guide developed by Jensen, Amos, and their colleagues includes a number of suggestions for how firms and labs can develop their own plans. Its first recommendation is to study the amount of people in the laboratory at any given time, and look for areas where one-way movement zones can be implemented, which may require staggered work shifts. Hands-free door openers should be utilized, restrooms should be converted to single occupancy if possible, and any large staff meetings should be held virtually. Lab teams should keep in mind that productivity may be reduced if teams cannot work in close proximity to each other, and should therefore plan accordingly. Training plans and quick communication should be available to employees, and need to be formally documented. Lab managers should prioritize which projects to pursue and how many resources to assign in order to maximize efficiency. Contingency plans must be developed now, in case the supply chain breaks down in the future or the lab must once again be shut down due to recurring small waves of coronavirus, a “monster wave,” or a persistent health crisis. HEPA filtration and modified air flow systems should also be considered, due to the respiratory nature of COVID-19 and the as-yet scientific uncertainty regarding the human infectious dose.

The guide also contains a case study taken from the University of Virginia, School of Medicine biomedical research lab. This 30,000 sq. ft. lab, designed by Cooper Carry in 2019, serves as a test case to illustrate some of the points contained in the guide, such as the implementation of physical barriers and one-way corridor traffic in order to minimize exposure. A “hierarchy of controls” diagram lists strategies designed to keep workers safe in the lab—elimination (physically remove the hazard) and substitution (replace the hazard) will not be available until a vaccine is developed, so for the time being lab managers should utilize engineering controls (isolate people from the hazard), administrative controls (change the way people work), and PPE (protect the worker with apparel) for their labs to operate at safe levels.

“When we first started brainstorming this, [we realized] there are universal things about a lot of labs. If you’re working in a wet lab, modulars are generic footage. There are certain kinds of social distancing things that can be applied across the board for laboratories,” Amos says. Scheduling conversations between lab leadership, the ES&H department, and design professionals about what level of safety you’re trying to achieve is crucial, he says, and discussions should include how to occupy spaces, social distancing and masks, and tasks such as measuring employees’ temperatures and adjusting lab equipment where necessary. “It depends on what appetite the group has for change management,” he says.

What does the future hold for lab design and lab operations, as COVID-19 restrictions ease off and the danger of the virus has largely passed? Will things ever go back the way they were before early 2020, or must all lab users and design/build professionals adapt to a new normal? That, says, Jensen, is the $64,000 question: “It really could be significant. The current model that we all know and have been designed to for decades now is very dense,” he says. “It’s all about efficiency and density, packing a ton of grad students into workstations, a ton of work equipment side by side. Everything right now relies on that. It could be significant.”